A courtroom in Nairobi became the stage for a public clash on Monday as the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) and the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) argued about a plea bargain meant to end the long-running graft case against former Migori governor Okoth Obado. The disagreement forced judges to slow the process and sent a clear message: even deals that look clean on paper can raise hard questions.

The DPP told the court it had struck a plea agreement after repeated negotiations with the accused and their lawyers. “After receiving written requests, the DPP directed the prosecution team to engage the EACC and defence lawyers in consultations. Three meetings were held, leading to a consensus to settle the matter through a plea bargain,” the ODPP said in court filings. As part of the deal, the state says it recovered assets worth about KSh235 million from Obado and co-accused.

EACC lawyers, however, told the judge they had not signed the written plea agreement now before the court. They said commission officials had attended talks but were never given the final draft to review or to seek instructions from their leadership. “We requested for the draft, but the same was not availed to us. We have therefore not had an opportunity to go through it or seek instructions,” the commission told the court, arguing that the omission undermined the dispute-resolution process the agencies had agreed.

The difference matters. The ODPP says it has constitutional authority to withdraw or settle charges under the Criminal Procedure Code and its prosecutorial rules. Defence counsel for Obado backed that view, telling the court that the DPP may lawfully enter into plea bargains and that EACC’s signature is not mandatory for the withdrawal of criminal charges. The defence argues the talks included a parallel civil settlement and that the criminal file can be closed once agreed terms are met.

For observers, the row raises two practical questions. First, did all investigating agencies truly buy into the terms before the DPP presented the deal? Second, does the recovered property and the plea bargain serve public interest and the rule of law? The ODPP says the assets surrendered — eight parcels of land and vehicles among them — equal roughly three times the contested sum and are a win for recovery efforts. Critics worry that backroom deals can deny the public a full accounting.

Legal experts say the court now faces a narrow test: it must decide whether the withdrawal application meets the tripartite public-interest test in Article 157(11) of the Constitution. The court will weigh the administration of justice, public interest and the risk of abuse. If the judge accepts the DPP’s view, the criminal case may be halted and the plea terms enforced. If not, prosecutors must return to court with clearer proof that all investigating agencies agreed.

What happens next is procedural but consequential. The judge will review the records, hear final submissions and rule on whether the withdrawal stands despite EACC’s objections. Whatever the outcome, the episode will be measured by the public not only in legal terms but in trust: do citizens feel the state recovers stolen public wealth and holds officials to account, or do they see deals that let powerful accused persons escape full scrutiny?

Either way, the case underlines a wider truth: anti-corruption victories live or die on process. Recovery of assets matters, but so does transparency. For Kenya, that balance is now the task before the court.

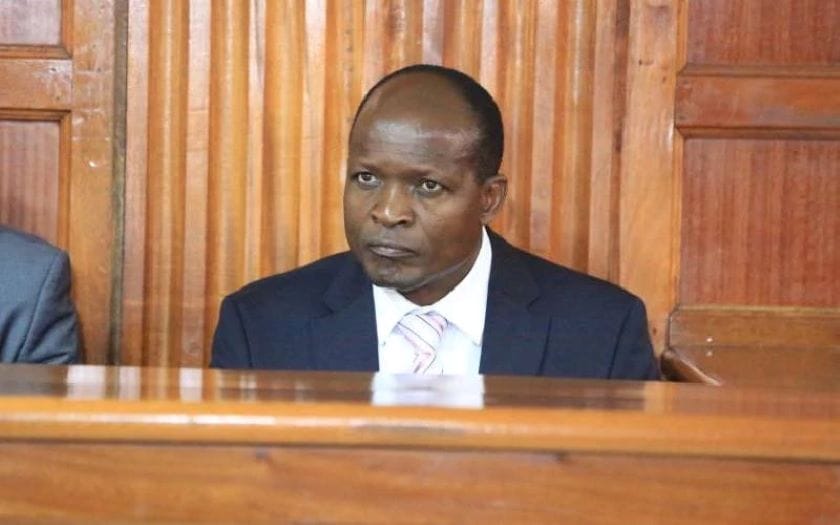

Featured image via Screengrab