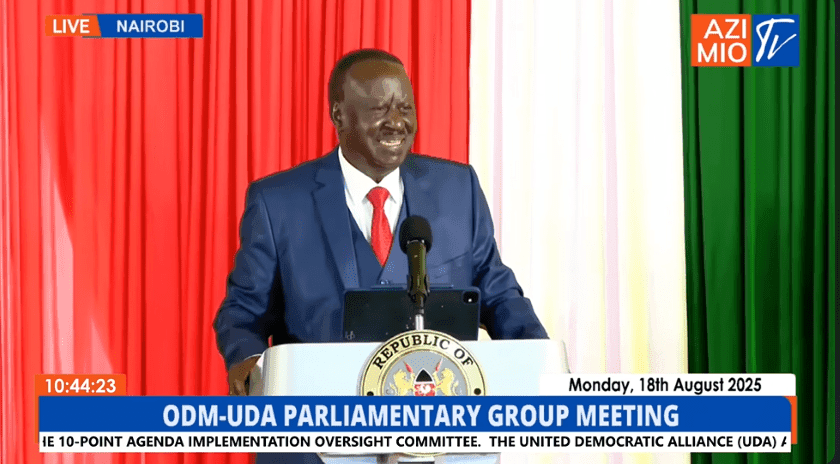

When Raila Odinga told MPs on Monday that the National Government Constituency Development Fund (NG-CDF) should be scrapped, the room erupted. Some lawmakers jeered. President William Ruto had to signal for calm so Raila could finish his speech. The moment made plain how charged the CDF debate has become.

Raila’s case is short and sharp. He says MPs should make laws and oversee government work, not run development projects. “Constituency is not an element of devolution… If you are involved in the construction of schools and roads, who is going to oversight you?” he asked, pressing that counties should deliver local projects while national MPs stick to oversight.

That view split the house. Supporters of CDF say the fund brings immediate benefits to local areas, classrooms, bursaries and small roads, and reaches people fast. Mumias East MP Peter Salasya pushed back on critics, calling CDF tightly controlled and urging probes if misuse is suspected. Salasya said bursary committees, not MPs, handle cash releases and demanded proof before sweeping judgments.

But recent audits give Raila ammunition. The Auditor-General flagged gaps and unexplained bursary payments worth billions, a finding that revived questions about oversight and leakages. A Standard investigation highlighted KSh 4.1 billion in bursary anomalies across several constituencies, showing stalled projects, stale cheques and unsupported spending. Those figures fuel the argument that a fund handled outside strong county systems can be vulnerable.

So which side has the stronger point? Put plainly: both do. CDF has delivered quick, visible projects that voters notice. That political visibility helps MPs and communities alike. But the audit shows weaknesses in record-keeping and accountability that are worrying. Moving funds to counties could reduce duplication and place development work with local planners, but it could also slow help to needy families if counties are not ready.

Why were MPs so angry? Partly because CDF is tangible power and money in constituency hands. MPs argue the fund lets them respond fast to local needs and ensures opposition areas get projects too. Opponents see that same power as a “cash cow” that can erode oversight and fuel corruption. The jeering in the meeting was less about policy theory and more about stakes: who controls money on the ground.

What to watch next: Parliament will debate the Auditor-General’s findings and proposed CDF reforms. Lawmakers may push to entrench CDF in the Constitution or to tighten controls and move functions to counties. Either road will need stronger audit systems, public participation, and clear rules that separate oversight from implementation.

Public mood is split. Some X users call Raila’s move timely and overdue; others say scrapping CDF is political posturing that will hurt local schools and bursaries.

He is right. The day CDF itatoka mikoni mwao, tutakuwa sawa

— Felix (@Kasitif) August 18, 2025

You MPs are righting against any call for disbanding NGCDF, not because of Kenyans or in the interest of Kenyans, but purely because of it being removed from your influence and control.

— OPK (@pquatch) August 18, 2025

And are passing laws to prevent prosecution and protect themselves . The legislature is a cancer. The whole system has failed

— DedanK (@kmdedan) August 17, 2025

At heart, the debate is simple: Kenyans want development that works and money that is accountable. Fixing the CDF question will need facts, not slogans — and actions that protect both service delivery and public funds. For voters, the question remains: will changes bring better schools and clinics, or will they just move where the money leaks?

Featured image via screengrab