A single, fragile jawbone has rewritten a chapter of deep time. In southern Chile, scientists unearthed a mouse-sized mammal that lived alongside dinosaurs about 74 million years ago. The little creature, named Yeutherium pressor, weighed roughly as much as a small apple — about 30–40 grams — yet its teeth tell a loud story about life on ancient southern continents.

The fossil is tiny: a partial upper jaw with one full molar and parts of two others. But the teeth are well preserved, and their shape shows this animal ate hard or crushed food — maybe seeds, tough plants or armored insects. From those dental clues, researchers placed the mammal among other small Mesozoic mammals known from South America, revealing links between distant fossil records.

Why does a single jaw matter? Long ago, southern South America lay closer to the South Pole. Winters were cold and daylight varied with the seasons. Finding a small, specialized mammal so far south shows that Mesozoic ecosystems were not simple or uniform. Instead, animals were adapted to a wide range of climates and niches — even in places that seemed hostile. This discovery fills a big blank on the map of ancient life and shows that tiny mammals were more widespread and diverse than scientists expected.

The find also matters for how scientists study evolution. Teeth carry clear signals about diet and lifestyle, and good teeth help paleontologists place fossils on the mammal family tree. This jaw helps connect southern groups to relatives in other regions, so researchers can trace how mammal lineages spread across ancient Gondwana. It also stretches our understanding of who survived — and who did not — at the end of the Cretaceous, when a mass extinction reshaped life on Earth.

There is a second lesson here about fieldwork. Remote outcrops, patient digging and careful lab work turn a bit of bone into a new idea about the past. The Dorotea Formation where this jaw was found may hold more specimens that tell us how small mammals lived, nested and fed in high-latitude worlds.

The tiny jaw is a reminder: big scientific shifts sometimes start with small fragments. As teams return to the site, we may learn not only what Yeutherium ate, but how it lived its short life under ancient southern skies. Could more finds show that small mammals were quietly thriving in places we once thought empty? The answer promises to redraw parts of Earth’s deep story.

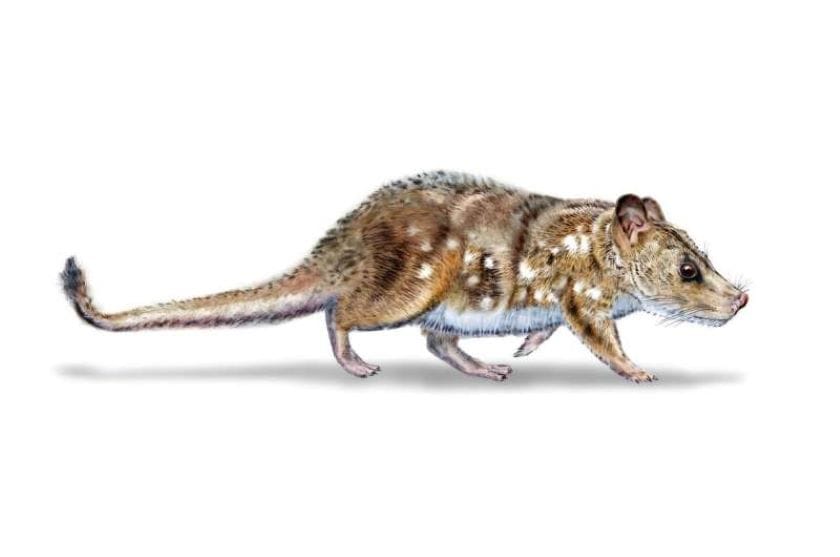

Featured image courtesy of Mauricio Alvarez